الوحدة 7

اكتشاف الثغرات التلقائي

آخر تحديث في: 28 ديسمبر 2024

GitHub تعديل هذه الصفحة علىالوحدة 7

آخر تحديث في: 28 ديسمبر 2024

GitHub تعديل هذه الصفحة علىيركّز مسار التعلّم هذا على الاكتشاف اليدوي للثغرات في تطبيقات الويب، وهذه المهارة ضرورية لفهم الثغرات وتمنحك أيضًا الأدوات اللازمة للعثور عليها في أي موقع. لكن هناك العديد من الأدوات التي يمكن أن تُساعد في اكتشاف الثغرات الأمنية واستغلالها في تطبيقات الويب، لكن لهذه الأدوات لها مزايا وعيوب على حد سواء ومن الأفضل استخدامها بالاقتران مع الاختبار اليدوي. يستعرض هذا الموضوع الفرعي عددًا من الأدوات المتاحة مجانًا وكيفية استخدامها بفعالية.

بعد الانتهاء من هذا الموضوع الفرعي سيتمكن الممارسون من معرفة كيف ومتى يستخدمون مختلف أدوات فحص الثغرات لتطبيقات الويب بشكل مناسب، بما في ذلك:

يستكشف هذا الموضوع الفرعي ثلاث فئات من أدوات أتمتة تطبيقات الويب، كما سيناقش ما تفعله وما تجيده وما لا تجيده وكيفية تحقيق أقصى استفادة منها، وسنقسم المساحة إلى ثلاث فئات عامة:

تشمل هذه الفئة الأولى الأدوات التي تفعل ذات الأمور التي يفعلها البشر للعثور على نقاط ضعف جديدة في تطبيقات الويب، حيث تفحص الموقع وتعثر على المدخلات وترسل البيانات الضارة إلى تلك المدخلات وتحاول اكتشاف متى تسببت هذه البيانات في ثغرة أمنية. ومن الأمثلة على هذا النوع من أدوات فحص تطبيقات الويب هي زد أتاك بروكسي من سوفتوير سيكيوريتي بروجكت ولكن هناك العديد من الأمثلة الأخرى بما في ذلك ماسح بيرب برو (Burp Pro) وإتش سي إل آب سكان (HCL AppScan)، وما إلى ذلك.

عادةً ما تعمل هذه الأدوات عن طريق “تتبع الارتباطات” أولاً على موقع الويب المستهدف حيث ستتبع كل رابط في كل صفحة وتحاول إنشاء خريطة كاملة للموقع. بعد ذلك ستعثر على كل معلمة تم إرسالها إلى الخادم وتستبدل تلك المعلمة ببدائل “عشوائية” مختلفة. ومع عودة كل استجابة ستبحث أداة المسح عن الخصائص التي تُشير إلى نجاح الهجوم. على سبيل المثال، قد يقوم محرك المسح باستبدال معلمة بما يلي<script>var xyz="abc";</script>. عندما تعود استجابة بروتوكول نقل النص التشعبي، ستقوم أداة المسح بتحليل لغة تمييز النص التشعبي للصفحات وإذا رأت عنصر البرنامج النصي ذلك في شكل كتلة جافا سكريبت في الصفحة ستعلم أن الإدخال معرض لثغرة البرمجة النصية عبر المواقع.

يستخدم الناس ماسحات تطبيقات الويب لسبب وجيه، فهي تجد الثغرات بسرعة وفعالية. وسيقوم فاحصوا أمان تطبيقات الويب ذوي الخبرة باستخدام الماسحات كجزء من تقييماتهم بغض النظر عن سنوات خبرتهم العديدة، حيث توجد بعض الأشياء التي تُجيدها ماسحات تطبيقات الويب.

تتمثل القوة الأكبر لهذه الأدوات في العثور على ثغرات المتعلقة بالتحقق من صحة البيانات. تُعدّ الماسحات ممتازة في العثور على مشكلات التحقق من صحة البيانات السائدة مثل البرمجة النصية عبر المواقع وحقن لغة الاستعلامات البنيوية، ولكن أيضًا المشكلات غير المشهورة مثل حقن البروتوكول الخفيف لتغيير بيانات الدليل (LDAP) وتحويل لغة صفحات الأنماط الموسعة (XSLT) وما إلى ذلك، وأسباب ذلك بسيطة.

تستخدم بعض الماسحات حتى سلاسل بيانات عشوائية فريدة لكل إدخال بحيث يمكنها اكتشاف الإدخال الذي تم في مكان واحد وعرضه في مكان آخر، وبشكل عام يجب أن يجد الذي تم تكوينه بشكل صحيح المزيد من مشكلات التحقق من صحة البيانات خلال فترة زمنية أقل من إنسان عالي المهارة.

من المجالات الأخرى التي تتفوق فيه الماسحات هو العثور على مشكلات التكوين وبالأخص تلك الموجودة في مجموعة فرعية صغيرة فقط على الموقع. في حال كان الموقع يستخدم رموز تزييف طلب المواقع المشتركة في كل شكل، ولكن نسي المطورون ذلك في أحد أقسام الموقع، فمن المرجح أن يتجاهل الفاحص البشري هذا الخطأ، ولكن من شبه المؤكد أن أداة المسح ستجد الرمز المفقود وتُبلغ عنه. كما هو الحال مع التحقق من صحة البيانات، تحتوي الماسحات على قواعد ضخمة من الاختبارات تُطبق على كل طلب واستجابة.

على الرغم من نقاط قوتها تعاني أدوات المسح أيضًا من نقاط ضعف متعددة، ولكن بعض الحالات قد لا يكون من المناسب حتى استخدام أداة مسح لاختبار مواقع معينة. وفيما يلي بعض أكبر المشكلات المتعلقة بماسحات تطبيقات الويب.

هناك العديد من المشكلات من المحتمل أن تُعاني منها طريقة عمل الماسحات والتي قد تتسبب في عدم اكتمال اختبار كامل على الموقع في الوقت المناسب.

أولها هي أن العديد من المواقع تتطلب من المستخدمين تسجيل الدخول، ويمكن تكوين الماسحات باستخدام معرّف جلسة تم تسجيل الدخول إليه أو باستخدام برنامج نصي يُقدم نموذج تسجيل دخول أو طرق مصادقة أخرى. يمكن أيضًا تهيئتها للكشف عن وقت تسجيل خروجها من الموقع، ولكن غالبًا ما يكون هذا التكوين عُرضة للخطأ. إذا تم تكوين أداة المسح بشكل غير صحيح، فقد لا تقوم بتتبع ارتباطات كامل الموقع أو قد لا تكتشف متى تم تسجيل خروجه دون أن استكمال الاختبار بشكل صحيح. في الحالات الشديدة قد تحتوي المواقع على ميزات مضادة للأتمتة تجعل المسح مستحيلًا تقريبًا.

وهناك مشكلة أخرى تتمثل بأن الماسحات لا تُميز دائمًا بين الصفحات المختلفة تمامًا مقابل الصفحات التي تبدو مختلفة فحسب. على سبيل المثال، في منتدى عبر الإنترنت من السهل على الإنسان أن يرى أن كل سلسلة على منتدى هو في الحقيقة الصفحة الأساسية ذاتها مع بيانات مختلفة. لكن قد تكتشف أداة المسح التلقائية أن سلسلتين هما صفحتا ويب مختلفتان تمامًا وأنه يجب اختبارهما بشكل منفصل، وفي المواقع الكبيرة قد تواجه الماسحات مشاكل في بعض الأحيان في اختبار صفحة واحدة تبدو وكأنها صفحات مختلفة بالنسبة لأدوات المسح وتقضي ساعات أو أيامًا في إجراء اختبارات مكررة.

ومن ناحية أخرى قد تكون هناك صفحات أو معلمات لا تكتشفها أداة تتبع الارتباطات لسبب أو لآخر، وإذا لم تكتشف أداة المسح معلمة أو فاتته أقسام من الموقع، فمن البديهي أنه من المحتمل أن يُفوّت ثغرات متعلقة بتلك الصفحات أو المعلمات.

يمكن حل جميع هذه المشكلات من خلال المراقبة الدقيقة لسلوك أداة المسح وتغيير تكوينات المسح، وفي حين أنه من الممكن تمامًا توجيه أداة مسح إلى موقع ويب وتشغيل الفحص، من المهم إكمال اختباري الاكتشاف والمصادقة على الأقل قبل بدء الفحص لأجل الوصول إلى أفضل النتائج.

تتمثل إحدى نقاط قوة أداة المسح في أنها تعمل بسرعة كبيرة، ولكن يمكن أن تُسبب هذه القوة مشاكل.

إذا تسبب إرسال طلب ما بتنفيذ إجراء ما خارج الموقع، فقد تقوم أداة المسح بتنفيذ هذا الإجراء آلاف المرات، وقد تشمل الأمثلة على التأثيرات الخارجية إرسال رسالة نصية قصيرة (والتي قد تُكلف مالك الموقع أموالًا) أو إرسال بريد إلكتروني (فتخيل أن يفتح شخص ما بريده الوارد ليرى عشرات الآلاف من رسائل البريد الإلكتروني)، وطباعة تذكرة طلب في مستودع وما إلى ذلك.

كذلك الأمر من حيث عدم امتلاك بعض المواقع الموارد اللازمة لمواكبة أداة المسح، وبالنظر إلى عدد المرات التي تتعرض فيها مواقع الإعلام المستقلة ومواقع المجتمع المدني لهجمات حجب الخدمة فقد يكون هذا أمرًا من المهم اكتشافه. ولكن تعطل الموقع سيمنع إجراء اختبارات الثغرات الإضافية.

يمكن التخفيف من حدة كلا هذين الأمرين جزئيًا من خلال المناقشات مع مالك الموقع ومن خلال الانتباه أثناء اختبار الاكتشاف وتكوين أداة المسح بشكل صحيح، فعلى سبيل المثال، تحتوي جميع الماسحات الرئيسية على طرق لاستبعاد صفحات معينة من عمليات المسح وللتحكم في مدى سرعة المسح. ولكن لا يمكن أبدًا تجاهل خطر تأثير أداة المسح على الموقع أو الأنظمة المرتبطة به.

في حين تُجيد الماسحات اكتشاف بعض أنواع الثغرات الأمنية إلا أن هناك أنواعًا أخرى يكاد يكون من المستحيل اكتشافها.

يُعدّ من بين أهمها ثغرات منطق العمل الحقيقية، حيث تقوم الماسحات فقط بتنفيذ البرامج النصية ولا “تفهم” كيفية عمل المواقع، ولن تفهم أي أداة مسح أهمية خطأ التقريب في التحويلات المالية أو أهمية حذف حقل يُفترض أن يكون مطلوبًا في نموذج.

وبهذا السياق لا تميل الأدوات الآلية إلى إجادة اكتشاف ثغرات التخويل، وعلى الرغم من وجود مجموعة متنوعة من الأدوات للمساعدة في اختبار التخويل لا تكتشف الماسحات عمومًا تلقائيًا أنواع الثغرات الأمنية هذه.

قد تنتج الماسحات أيضًا الكثير من النتائج غير المفيدة، ففي بعض الحالات قد يكون البرنامج النصي للكشف عن الثغرة الأمنية غير كامل مما يؤدي إلى قيام أداة المسح بالإبلاغ عن مشكلة في حالة عدم وجودها. وفي حالات أخرى قد تقوم أداة المسح بالإبلاغ عن أشياء قد يعتقد مؤلف الأداة أنها مثيرة للاهتمام أو ذات قيمة ولكنها ليست مهمة في سياق الموقع الذي تختبره. في جميع الحالات عليك إعادة تكرار نتائج أداة المسح يدويًا وفهمها تمامًا قبل إضافتها إلى تقريرك.

بشكل عام يجد ممارسو تقييم أمان تطبيقات الويب أنه من الأكثر فعالية استخدام الأداة من عدمها، ونظرًا لأن نقاط قوتها مقنّعة للغاية، يستحق الأمر قضاء الوقت لتكوين عمليات المسح ومراقبتها.

في جميع الحالات عليك إكمال الاكتشاف والمصادقة قبل استخدام أداة المسح. بما أنك جديد في هذا المجال، عليك التدرب على استخدام أداة مسح على مواقع ويب مختلفة وقراءة وفهم خيارات تكوين أداة المسح ومؤشرات التقدم، لذا حاول فهم كيفية عمل الموقع قبل إطلاق الماسح عليه.

سيقوم بعض الممارسين بمسح الصفحات بشكل فردي متخطين مرحلة “تتبع ارتباطات” ضمن المسح، ويسمح ذلك بالتخفيف من العديد من مشكلات المسح ولكنه يفوت أيضًا قدرة متتبع الارتباطات على العثور على المحتوى الذي ربما فاتك، كما أنه يتطلب جهدًا أكبر ولكن يمكن أن يكون فعالًا جدًا في المواقع التي يصعب على أداة المسح الوصول إليها والمواقع الأكثر هشاشة.

يمكن أيضًا مسح الموقع بأكمله في وقت واحد، ومن الجيد عمومًا استخدام مستخدم تطبيق ويب منفصل لهذا الفحص بحيث لا تتداخل البيانات عديمة الفائدة من الفحص مع اختبارك المنتظم. وتأكد أيضًا من أن الحساب الذي تستخدمه يتمتع بحق الوصول الكامل إلى الموقع. يجب أن تُحاول خلال سير الفحص تحقيق توازن بين مراقبة الفحص عن كثب بما يكفي لملاحظة المشاكل ولكن أيضًا أن تحاول قضاء معظم وقتك في إجراء الاختبار اليدوي.

يجب ألا تعتمد في كلتا الحالتين على أداة المسح بالكامل في اختبار التحقق من صحة البيانات أو أي فئة ثغرة أخرى، فعليك على الأقل إجراء عدة اختبارات على كل مدخل من مدخلات الموقع وإجراء بعض الاختبارات الشاملة على غيرها، حيث قد تواجه أداة المسح مشاكل خفية في اختبار الموقع لا تكون واضحة.

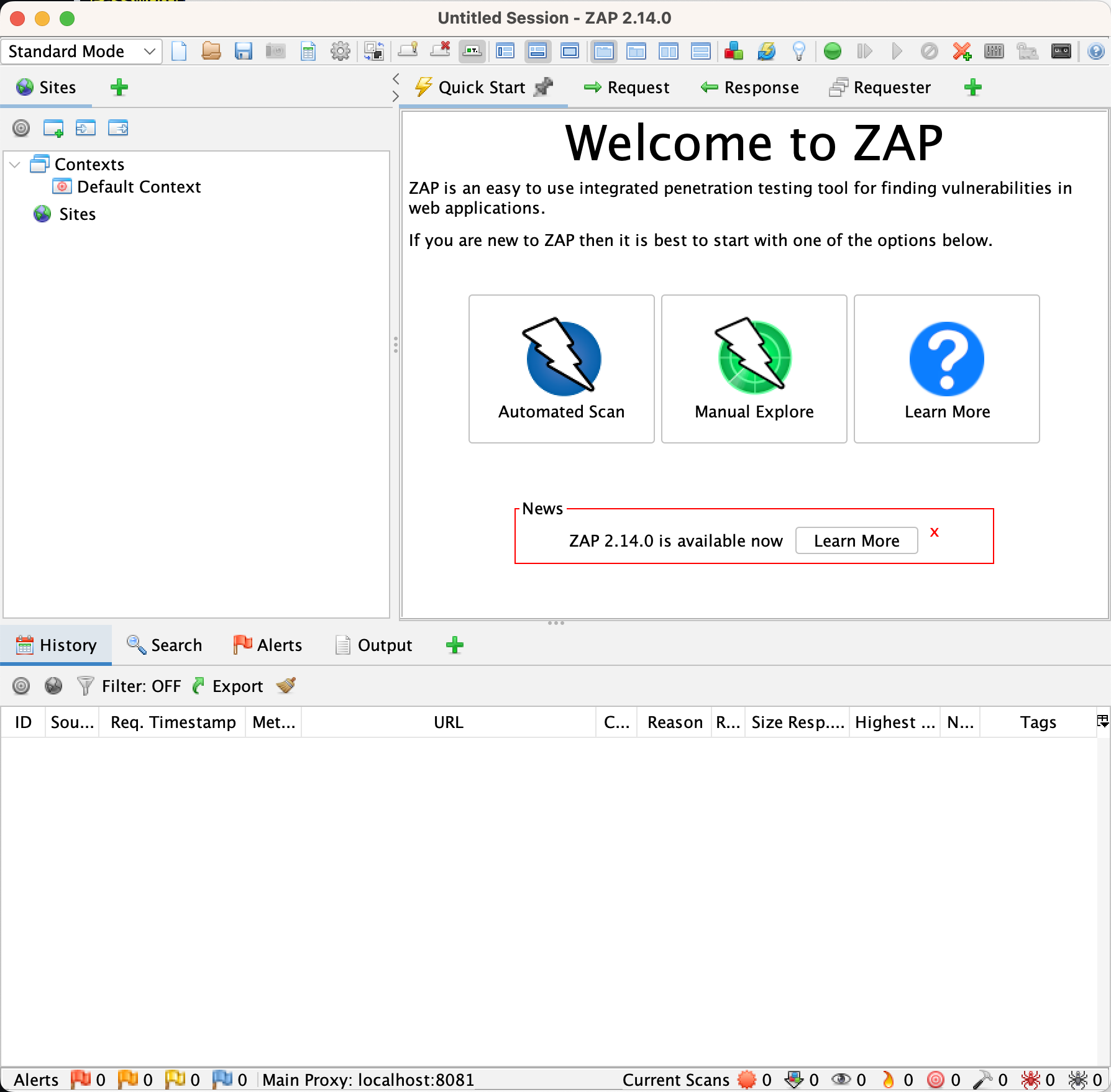

أداة زد أتاك بروكسي (التابعة لسوفتوير سيكيوريتي بروجكت) هو بديل مفتوح المصدر لبيرب، وبالرغم من تفضيل معظم المحترفين بيرب بروفشنل (Burp Professional)، يبقى زد أتاك بروكسي وكيلًا يفيه الكثير من القدرات ويتضمن أداة مسح لتطبيقات الويب. في هذه المرحلة يجب أن تكون ملمًا ببيرب سويت ومفاهيمه هي ذاتها بالنسبة لأداة زد أتاك بروكسي على الرغم من أن واجهة المستخدم مختلفة تمامًا.

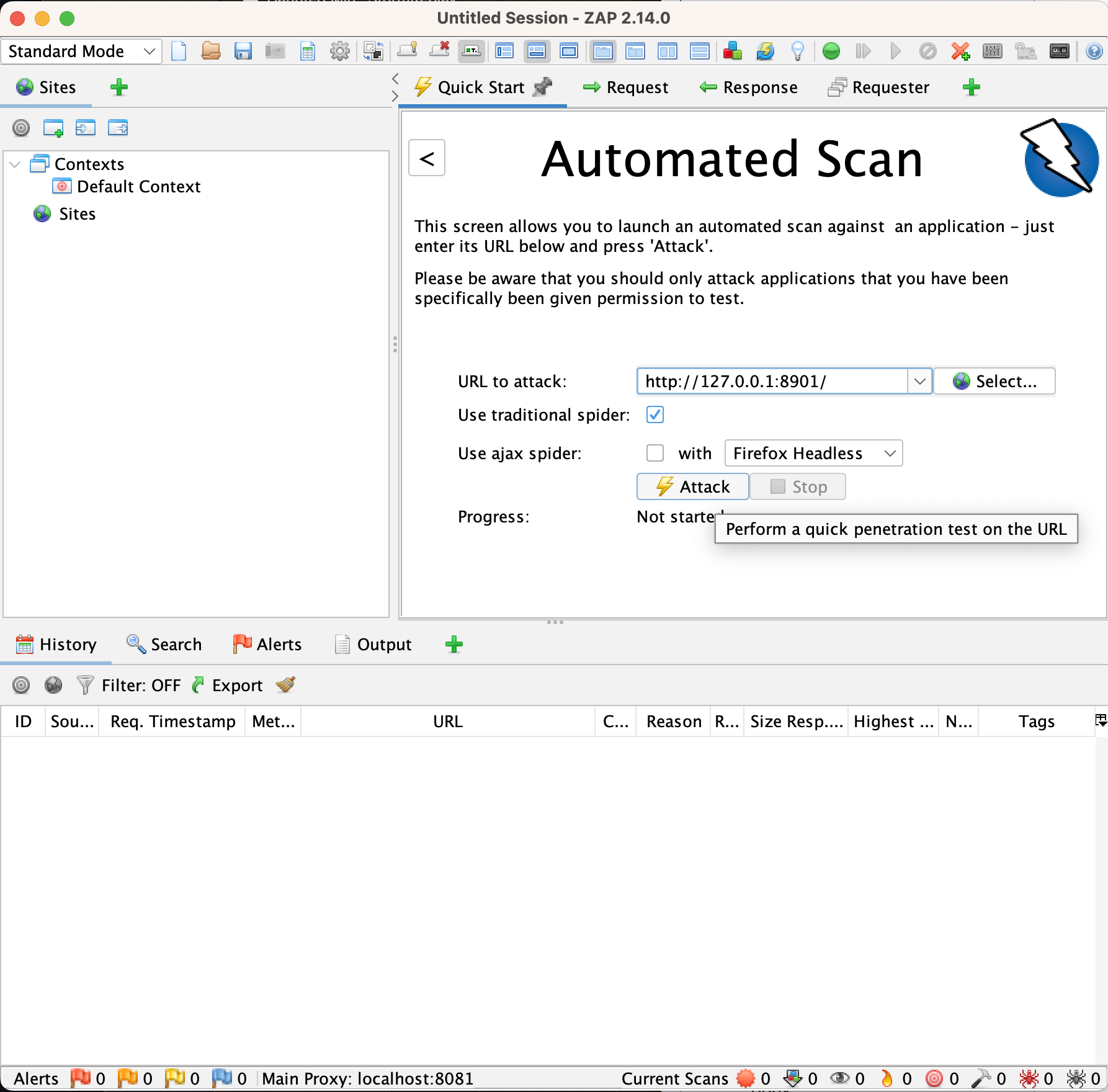

سنستخدم في هذا التمرين وحدة المسح من أداة زد أتاك بروكسي، ولتتعرف عليها تأكد أولاً من تشغيل نسخة من دي آي دبليو إيه، ثم ببساطة افتح أداة زد أتاك بروكسي وانقر على “الفحص التلقائي (Automated Scan)” وضع عنوان موقع الويب لصفحتك الرئيسية في دي آي دبليو إيه وانقر على “هجوم (Attack)”.

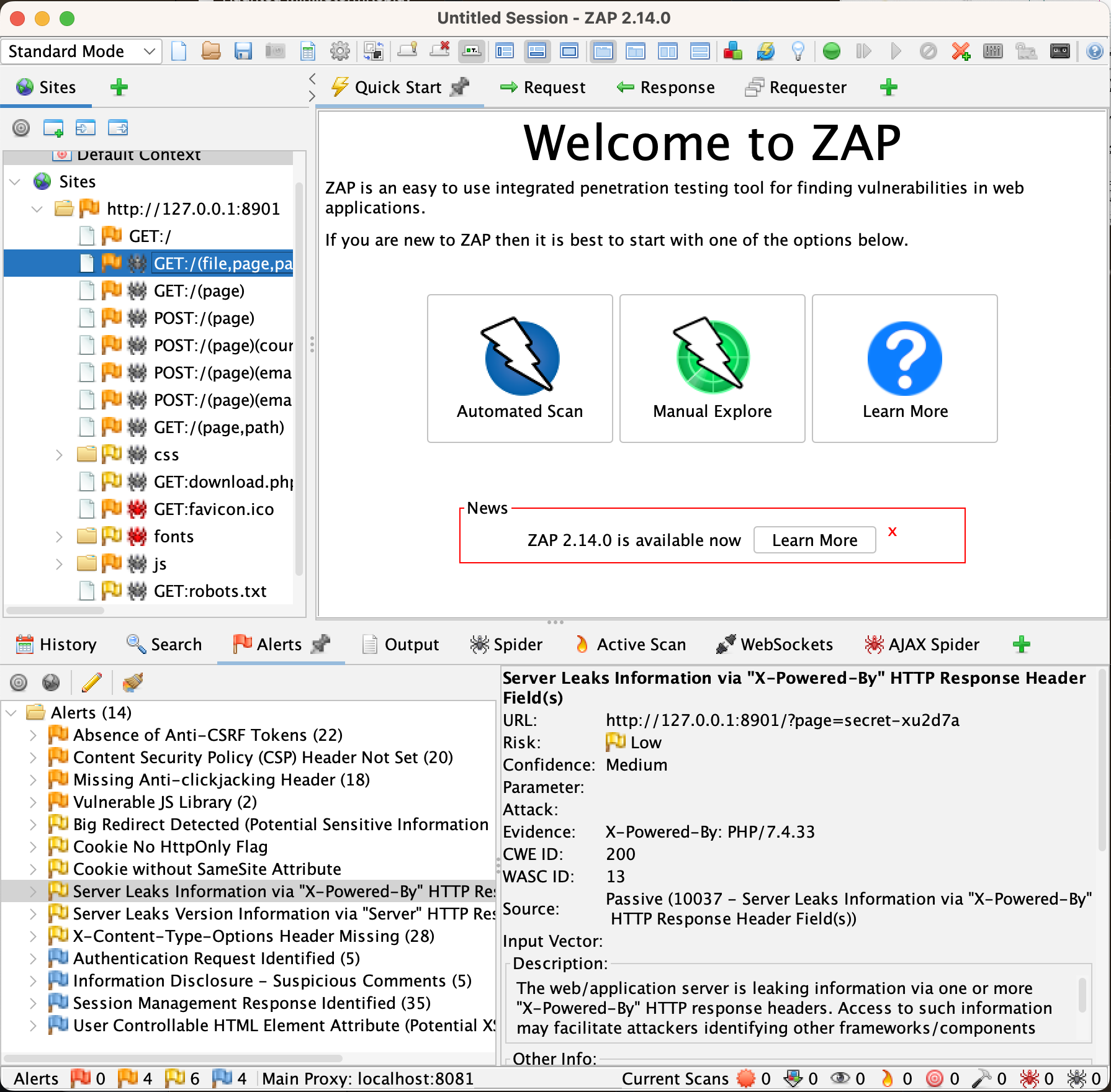

نظرًا لأن دي آي دبليو إيه تطبيق صغير يجب أن يكتمل هذا الفحص بسرعة نوعًا ما، وإذا لم يحدث أي خطأ فظيع فستلاحظ أن أداة مسح زد أتاك بروكسي وجدت بعض المشكلات. لكن ما لم تتغير أداة زد أتاك بروكسي بشكل كبير فقد تكون نتائج أداة زد أتاك بروكسي مخيبة للآمال إلى حد ما. قد تكون هناك مشكلات صغيرة وجدتها أداة زد أتاك بروكسي لم تجدها أنت ولكن من المفترض أن تكون أداة زد أتاك بروكسي فوتت معظم المشكلات الكبيرة التي وجدتها أنت.

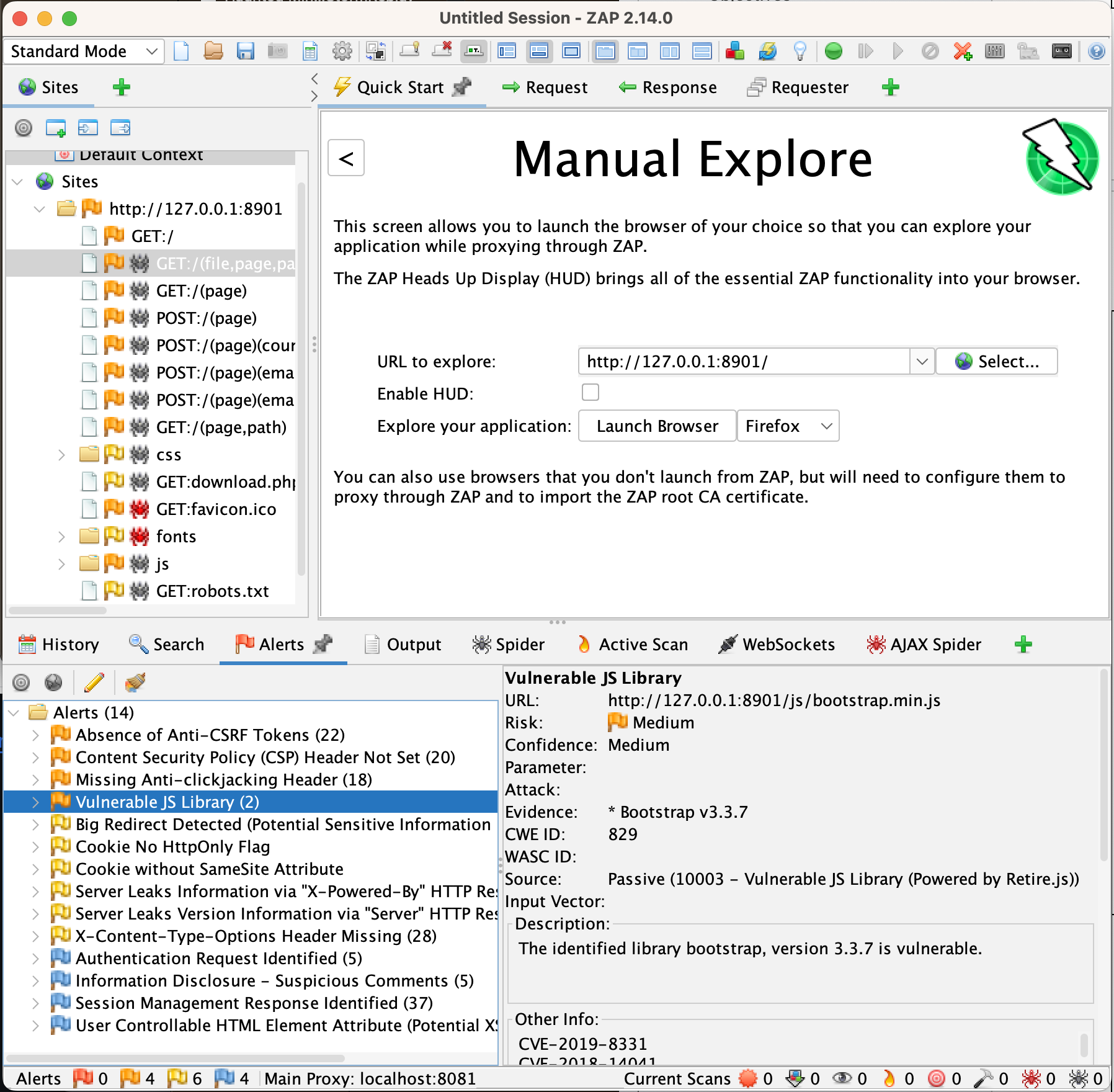

لنرَ ما إذا كان من الممكن تحسينها. انقر على زر “البدء السريع (Quick Start)” في شريط الأدوات الثانوي، ثم على “<” في النافذة أدناه، وبعدها انقر على “استكشاف يدوي (Manual Explore)” ثم ضع عنوان موقع الويب الخاص بدي آي دبليو إيه وانقر على “تشغيل المتصفح (Launch Browser)”.

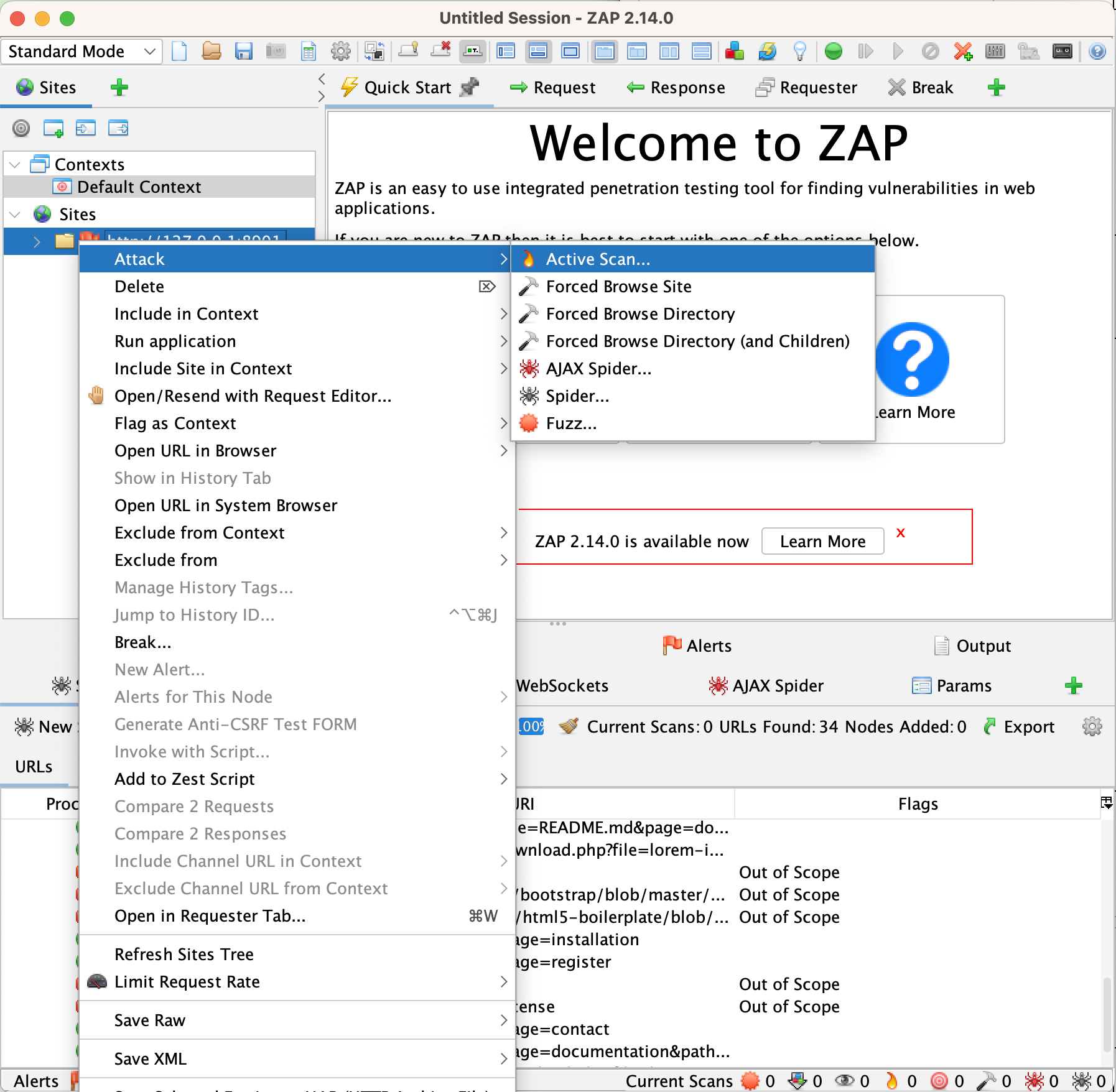

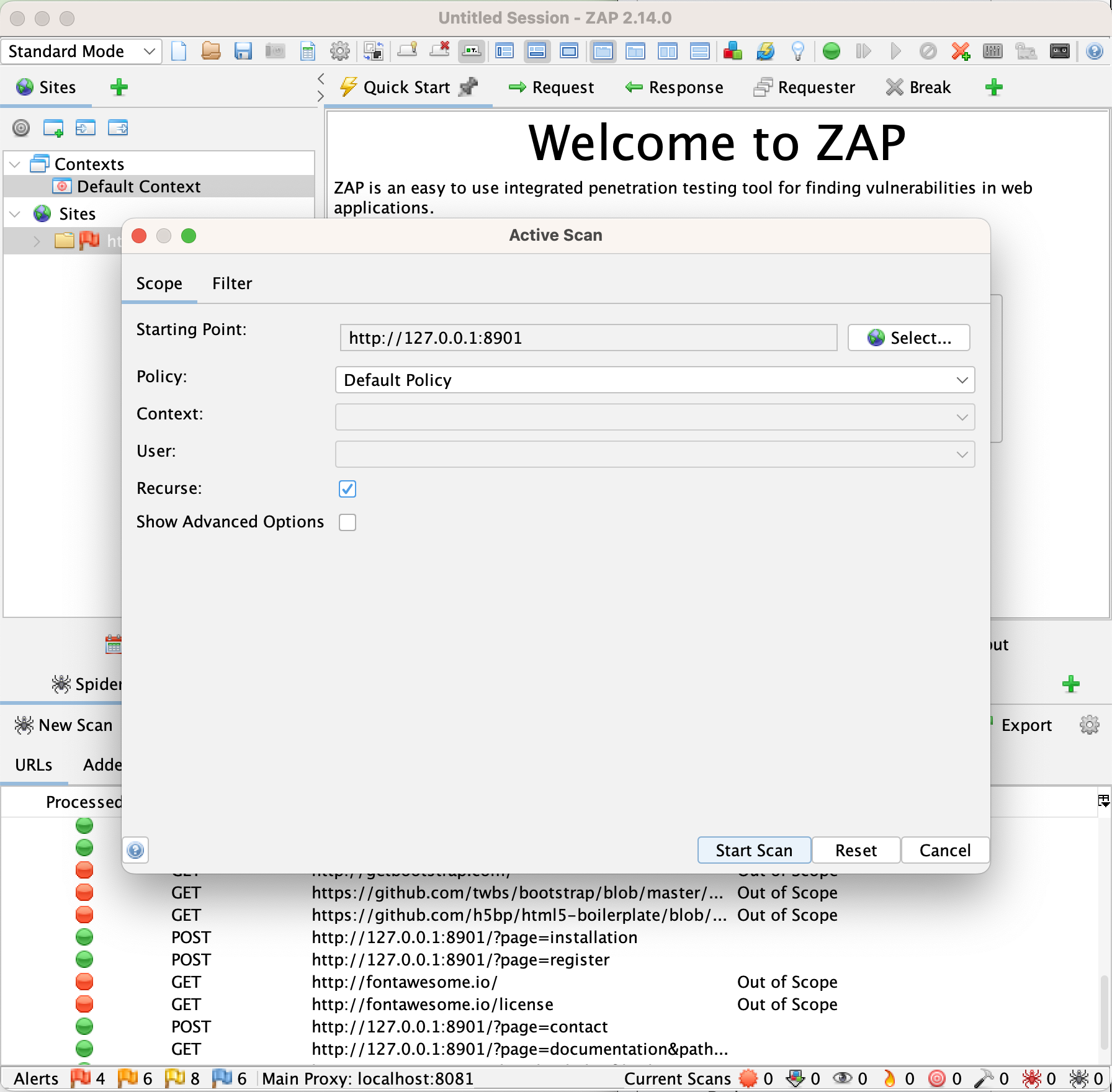

تصفح الموقع قليلاً وتأكد من تسجيل دخولك إلى الموقع بصفة مستخدم مشرف عند الانتهاء. والآن ارجع إلى أداة زد أتاك بروكسي وابدأ المسح بالنقر بزر الماوس الأيمن على موقع دي آي دبليو إيه في الشريط الأيسر وابدأ المسح النشط باستخدام الإعداد الافتراضي.

يجب أن يستغرق هذا الفحص وقتًا أطول بكثير وسيعطي نتائج أفضل مختلفة بشكل كبير. لم حصلَ هذا؟ يسمح بدء الفحص من موقع قمت بزيارته في قسم “المواقع” أداة المسح معلومات أكثر بكثير مقارنة بفحص تلقائي بالكامل، وفي الواقع قد تختلف النتائج التي تحصل عليها من أداة المسح اختلافًا كبيرًا استنادًا إلى كيفية استكشاف الموقع يدويًا قبل تشغيل الفحص.

جرّب استخدام الموقع وتشغيل عمليات المسح قليلًا ثم قارن النتائج من أداة زد أتاك بروكسي بالنتائج التي حصلت عليها من الاختبار اليدوي.

فكر في هذين السؤالين، ريثما نعود إلى سرد قوائمهما ضمن قسم التحقق من المهارة.

الفئة التالية من الأتمتة التي سنغطيها في الموضوع الفرعي هي الأدوات التي تساعد في الاستغلال بعد العثور على ثغرة أمنية، وفي حين أن هناك العديد من الأدوات لهذا الغرض، فإن الأداة الأكثر استخدامًا في تقييمات أمان تطبيقات الويب هي إس كيو إل ماب. وهي أداة قادرة على اكتشاف حقن لغة الاستعلامات البنيوية لمواقع الويب ولكنها تتألق حقًا في الاستغلال. قد تستغرق بعض تقنيات استخراج بيانات حقن لغة الاستعلامات البنيوية العشوائية عدة ثوانٍ لاستخراج معلومة من قاعدة بيانات. لكن يمكن لأداة إس كيو إل ماب أتمتة وتحسين معظم أشكال استغلال حقن لغة الاستعلامات البنيوية مما يوفر لك الكثير من الوقت.

يتمثل الاستخدام المستقل النموذجي لأداة إس كيو إل ماب في حفظ الطلب الذي استخدمته لتحديد حقن لغة الاستعلامات البنيوية في ملف نصي ثم تشغيل إس كيو إل ماب مع هذا الملف النصي مع استخدام علامة r-، ويمكنك بعدها تحديد المعلمة التي ترغب باختبارها باستخدام علامة p- ثم اختيار البيانات التي ترغب في استخراجها. بشكل عام من الأفضل البدء بخيار b- لاسترداد معلومات قاعدة البيانات ببساطة حيث ستحاول أداة إس كيو إل ماب التأكد من أن المعلمة المحددة عرضة لحقن لغة الاستعلامات البنيوية، ثم اختر تقنية استخراج بيانات تسمح لها باستخراج البيانات بأكبر قدر ممكن من الكفاءة. وقد يكون استخراج البيانات بطيئًا للغاية وفي هذه الحالة يجب أن تكون حذرًا بشأن مقدار البيانات التي تحاول استخراجها.

تجدر الإشارة إلى أنه إذا وجدت العديد من ثغرات حقن لغة الاستعلامات البنيوية في موقع ما فقد تسمح بسرعات مختلفة جدًا لاستخراج البيانات وستكون أي ثغرة حقن لغة الاستعلامات البنيوية تؤدي إلى التسبب بتضمين بيانات من قاعدة البيانات في استجابة بروتوكول نقل النص التشعبي أسرع بكثير من تلك التي تؤدي فقط إلى النجاح أو الفشل (كما هو الحال في صفحة تسجيل الدخول).

من بدائل أداة إس كيو إل ماب بشكل مستقل هو استخدام تكامل الوكيل لتشغيل إس كيو إل ماب مباشرة من الوكيل الخاص بك كما هو الحال في إضافة س كيو إل آي ب واي (SQLiPy) لأجل بيرب، حيث يؤدي هذا بشكل عام إلى تسريع تكوين إس كيو إل ماب ويوفر عليك بضع رحلات ذهابًا وإيابًا إلى وثائق إس كيو إل ماب.

من الموضوع الفرعي المتعلق بالإعداد يجب أن يكون تكون أداة إس كيو إل ماب مثبتة ولديك ويجب أن يكون لديك نسخة من دي آي دبليو إيه أيضًا. يجب أن تكون قد حددت بالفعل ثغرة واحدة أو أكثر من ثغرات حقن لغة الاستعلامات البنيوية في دي آي دبليو إيه، وباستخدام الأداة استغل إحدى هذه الثغرات لاستخراج بنية قاعدة بيانات دي آي دبليو إيه ثم استخرج قاعدة بيانات المستخدمين.

لاحظ أن أداة إس كيو إل ماب تتمتع بقدرات وخيارات تكوين تتجاوز ما تمت مناقشته هنا، وتأكد من الاطلاع على الوثائق لمعرفة خيارات الاستخدام.

لأغراض هذا الموضوع الفرعي نستخدم كلمات ماسحات الثغرات لتعني أداة تكشف عن الثغرات الأمنية المعروفة سابقًا بدلاً من أداة تكتشف الثغرات الأمنية الجديدة تلقائيًا، وتتضمن الأمثلة على الأولى أدوات مثل نيسوس (Nessus) وأوبن في إيه إس (OpenVAS)، بينما تشمل الثانية الماسح المدمج في بيرب برو وأداة زد أتاك بروكسي.

بينما تحاول أداتا نيسوس وأوبن في إيه إس كشف مجموعة واسعة من الثغرات، هناك أدوات أخرى متخصصة مثل نايكتو (Nikto) التي تحاول العثور على أخطاء تكوين خوادم الويب على وجه التحديد. وعلى الرغم من أن هذه الأداة لم يتم تحديثها منذ سنوات واستبدلتها عمومًا أدوات مسح الثغرات الأمنية التي تستخدم لأغراض العامة، توجد أداة مسح ثغرات تطبيقات ويب محددة تتميز عن غيره. تُسمى هذه الأداة دبليو بي سكان (WP Scan) وتُركز على العثور على ثغرات في مواقع ووردبرس، ونظرًا لأن هذه المواقع تتمتع بشعبية كبيرة بين المجتمع المدني ومواقع الصحافة المستقلة، فمن المفيد تغطيتها في مسار التعلّم هذا.

بدأت أداة دبليو بي سكان على شكل برنامج مفتوح المصدر ولا يزال إصدار سطر الأوامر منها كذلك ولكن توجد خيارات مدفوعة لأولئك الذين يريدون ميزات أخرى. تعمل أداة دبليو بي سكان بشكل أساسي بنفس طريقة عمل ماسحات الثغرات الأمنية الأخرى، وببساطة تُرسل الطلبات إلى الخادم وتحاول تحديد إصدارات البرامج المثبتة على هذا الخادم ثم تقارن تلك الإصدارات بقاعدة بيانات ثغرات. 🛠️ قم بتنزيل دي في دبليو بي (ستحتاج إلى استخدام داكر لنشره) وإذا كنت تستخدم جهاز ماك من آبل سيليكون فقد تضطر إلى إضافة “platform: linux/amd64” إلى كل خدمة في ملف docker-compose.yml.

قم بعدها باستخدم واجهة سطر أوامر دبليو بي سكان للعثور على ثغرات على الموقع، وإذا كنت قد قمت بتثبيت دبليو بي سكان عبر داكر على ماك أو ويندوز، فلن تتمكن من استخدام 127.0.0.1:31337 لتوجيه دي في دبليو ب على دبليو ب سكان. هذا لأن داكر يعمل في جهاز ظاهري ويعد مقابل عنوان 127.0.0.1 في الجهاز الظاهري هو الجهاز الظاهري نفسه وليس جهاز الكمبيوتر الخاص بك. عليك بدلاً من ذلك البحث عن عنوان بروتوكول إنترنت الشبكة المحلية لجهاز الكمبيوتر الخاص بك (على سبيل المثال ×××.196.168.0، ×××.×××.×××.10 وما إلى ذلك) واستخدمه.

ستحتاج على الأرجح إلى التسجيل للحصول على مفتاح واجهة برمجة التطبيقات على موقع دبليو بي سكان واستخدامه عند المسح على الرغم من أنه هذا الأمر غير مطلوب. إذا لم تحدد مفتاح واجهة برمجة التطبيقات ستقوم أدأة دبليو بي سكان بتحديد إصدارات ووردبرس وملحقاته وستخبرك بالإصدارات القديمة، وإذا استخدمت مفتاح واجهة برمجة التطبيقات سيخبرك عن الثغرات الموجودة في الموقع.

ناقش استخدامك لأداة زد أتاك بروكسي للمسح إس كيو إل ماب على دي آي دبليو إيه مع مرشدك. لماذا وجدت أشياء لم تجدها أداة زد أتاك بروكسي، ولماذا العكس أيضًا؟ اشرح له كيف تخطط لاستخدام الأتمتة لمساعدتك في اختبار مواقع الويب من الآن فصاعدًا؟

Web crawler

FreeAn overview of what a web crawler is and what it does.

Using Burp with sqlmap

FreeInstructions on how to integrate sqlmap with Burp for web application security testing.

Damn Vulnerable WordPress

FreeA specially designed WordPress installation intentionally vulnerable for testing purposes.

تهانينا على إنهائك الوحدة 7!

حدد خانة الاختيار لتأكيد إكمالك والمتابعة إلى الوحدة التالية.

تحديد الوحدة الحالية على أنها مكتملة وحفظ التقدم للمستخدم.

لقد أكملت جميع الوحدات في مسار التعلم هذا.