Module 2

Data Validation

Last updated on: 13 November 2024

Edit this page on GitHubModule 2

Last updated on: 13 November 2024

Edit this page on GitHubA common class of web application vulnerabilities relates to the way the app processes data supplied by users of the site. This class of vulnerabilities is commonly used by attackers to completely take over target websites, and often can be discovered via automated techniques. Understanding the mechanisms for data validation vulnerabilities is also extremely useful for demystifying complex security topics.

After completing this subtopic, practitioners should be able to do the following:

Our first class of web application specific vulnerabilities encompasses those related to data validation. There are many different kinds of data validation vulnerabilities, and they can occur in any system that processes input. Generally, these vulnerabilities occur when the application makes implicit assumptions about the length and/or content of data it’s sent. When the input is received and/or processed, the data “escapes” its intended context and becomes code in its new context. We’ll talk about how this works, its consequences, and how to fix the vulnerability for each specific type. Be sure to read through in order, as the sections build on previous ones.

The name “cross site scripting” is an artifact of how early XSS exploits worked. A better name might be “JavaScript injection,” but the old name remains for historical reasons. XSS occurs when a browser interprets user input as JavaScript. This allows an attacker to, to a limited extent, control the targeted person’s web browser in the context of the target website. The attacker can steal the targeted person’s cookies, allowing the attacker to impersonate them on the site. More than that, though, the attacker can automatically extract any of the targeted person’s data from the target website and can similarly perform actions on the target site as the user. Finally, the attacker can change the appearance of the website for the targeted person, for example popping up a fake re-authentication page that sends the user’s credentials to the attacker or prompting them to download malware purporting to come from a trusted site.

While this attack is powerful, there are limits. The attacker is limited to controlling the content of the target website within the context of the user’s browser. The attacker cannot interact with other websites, and their actions are limited by browser security features.

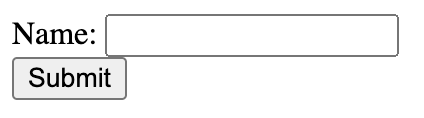

Mechanically, this attack works by a web application receiving user data, and then integrating that user data directly into a web page. Consider a discussion forum site that allows users to to pick a display name:

This rather un-fancy web page has the following HTML code:

<html><body><form>

Name: <input name="disp_name"><br>

<input type="submit">

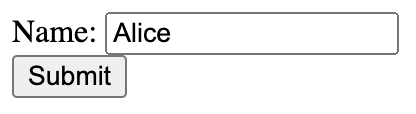

</form></html>When it receives a name from the user, it displays it in the form:

using the following HTML:

<html><body><form>

Name: <input name="disp_name" value="Alice"><br>

<input type="submit">

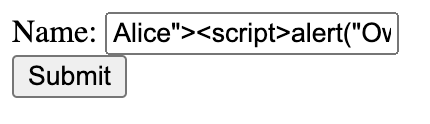

</form></html>So far so good. Now, what happens if the user enters some more tricky input, like:

Alice"><script>alert("Owned by Alice")</script><i q="When the web page is generated, it looks a bit different:

How did this happen?

Alice"><script>alert("Owned by Alice")</script><i q="The application simply takes the input from the user and places it verbatim into the HTML it generates, from the point of the view of the web application, and the web browser, it’s all just undifferentiated text.

<html><body><form>

Name: <input name="disp_name" value="Alice"><script>alert("Owned by

Alice")</script><i q=""><br>

<input type="submit">

</form></html>Note the "> after value="Alice". That tells the browser that the HTML input’s value attribute is completed, and then that the input tag is completed. Next, the text is a script tag that runs the JavaScript that pops up an alert box. Finally, the <i q=" is just some cleanup that prevents the web page from displaying the remnants of the original input tag.

<html><body><form>

Name: <input name="disp_name" value="Alice"><script>alert("Owned by

Alice")</script>

<i q=""><br>

<input type="submit">

</form></html>As it is, this demonstration of XSS doesn’t do anything malicious, and the only person who is affected is Alice herself. However, if our attacker Alice can cause someone else to see her display name, and her JavaScript does something malicious, then she’s got a real attack to perform.

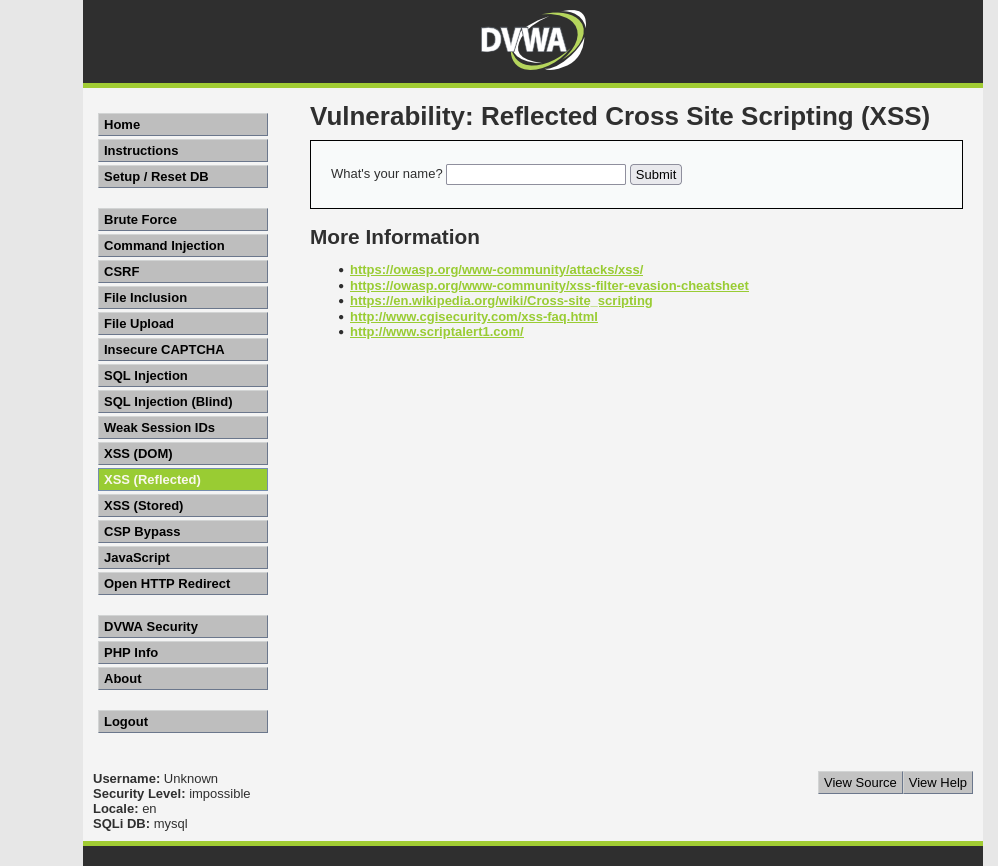

Log into your DVWA and make sure the security level is set to low (see the “Setup” section in the introduction of this learning path for more information on this). Navigate to the “XSS (Reflected)” section. The “What’s your name?” input is vulnerable to XSS. Try to enter a name that causes a JavaScript alert box to pop up when you click the “Submit” button.

If you get stuck on any DVWA exercise and want a hint, just click on the “View Help” button on the bottom right of the screen to receive hints.

To prevent XSS, the best technique to use is called output encoding. Note that in the above example, the attack was enabled through the use of the " and > characters. In the context of a web page, those characters control the structure of the page. In HTML, all such characters can be encoded, so that the web browser knows to display a double-quote or angle bracket, as opposed to modifying the structure of the page. In this case, if Alice’s data was output encoded before being integrated into the web page, it would generate the following HTML

<html><body><form>

Name: <input name="disp_name" value="Alice"><script>alert("Owned by Alice")</script><i q=""><br>

<input type="submit">

</form></html>which would display like this

Output encoding is dependent on the context that the data will be used in. For HTML, you would encode HTML entities in the data. For data that was going to be included into a block of JavaScript, a different encoding would be used. If user data was going to be used in a database query yet another type of encoding would be used. Web frameworks and libraries should have functions to perform output encoding for you; it’s better to use those (hopefully) mature functions than to try to write them yourself from first principles.

For a bit more on XSS, see the OWASP guide on XSS. For an in-depth exploration, see the Web Application Security Assessment learning path.

Where XSS allows user data to escape from its context and be interpreted as HTML and JavaScript in the victim’s web browser, SQL injection allows user data to escape from its context and be interpreted as SQL on the web application’s database. Most web applications use a back-end database to store and retrieve data. Typically, they will use SQL to perform this data access. SQL injection can occur where user data is interpolated into a query.

Since the attacker-controlled SQL is run in the server environment, SQL injection vulnerabilities are generally much more dangerous than XSS. While an XSS vulnerability allows an attacker to target other users, perhaps through some sort of social engineering, SQL injection can give the attacker read-write access to all user data on the site. The attacker can also read and write any other data stored in the database that the web application can assess. Frequently, the attacker can use the SQL access to gain the ability to run commands on the database server itself, gaining full remote access to the website’s back-end infrastructure.

How does SQL injection work? Consider a web application, where there’s a ticketing platform that lists the name, description, and version of each tool in a category. The user would also be submitting an id parameter; this might even be contained in the URL of the page making the request. Perhaps the code that generates the SQL that retrieves this data looks something like:

$sql = 'select productid, name, description, version from products where categoryid='+request_params['id']When a user sends an id parameter like 1 or 32, all is well, we get a query like:

select toolid, name, description, version

from tools

where categoryid=32However, the trouble starts when a curious user sends an id of 2-1, and notes that they get the same results as for an id of 1:

select toolid, name, description, version

from tools

where categoryid=2-1This shows the attacker that the application is vulnerable to SQL injection. It is interpreting their input as code (executing the expression 2-1) instead of data (looking for a category whose ID is literally “2-1”). After a bit of digging around, they send an id of -1 union all select 1, username, password, 1.0 from admin_users. This results in a SQL query of

select toolid, name, description, version

from tools

where toolid=-1

union all

select 1, username, password, 1.0

from admin_usersWhat this query does is look up all the tools that have a category id of -1 (which is probably none of them), and then add to that list the usernames and passwords of the ticketing platform’s admin users. The application then formats this as a nice, readable HTML table and sends it back to the user requesting the data. Not only will this allow the attacker to simply log into the ticketing system, but if any of those users reuse their passwords, then the attacker may be able to access other systems in the same organization.

Log into your DVWA and make sure the security level is set to low. Navigate to the “SQL Injection” page, and experiment with the input. Can you cause the page to return the list of all user accounts? Can you use the “union all” technique to retrieve data from other tables, such as the table called “information_schema.tables”?

Unlike with XSS, output encoding is not a reliable way to prevent SQL injection. Note that in the above examples, the attacker uses characters such as space and - to change the context of their data from that of data in the SQL query to that of the structure of the query itself. Some combination of type-aware input filtering and output encoding can prevent SQL injection in theory, but in practice this approach is very unreliable.

Instead, we can use a feature of every database engine that skips some of the initial parsing of the query entirely. This type of query is called a parameterized query, and using it is frequently called parameter binding. Instead of sending the database a string of text that contains both the structure of the query and the user’s data, we send one string that contains the structure of the query with placeholders in it for the data. Along with that string, we send the data for each placeholder. In this way, the user’s data is never parsed in a SQL context; no matter what they send, it will be treated exclusively as data. Not only does this protect against SQL injection, it makes the database queries slightly faster.

For a bit more on SQL injection, see the OWASP guide on it. For an in-depth exploration, see the Web Application Security Assessment learning path.

This class of vulnerabilities involves the user sending a web application that subverts the application’s interactions with the filesystem. With this type of vulnerability, the attacker can influence or control the pathname of a file that the web application is reading from or writing to, potentially giving the attacker full access to any file that the web server can read or write. Depending on what’s stored on the web server, this may give different abilities to an attacker. However, popular targets are configuration files, which often contain credentials for databases and other external network services, and the source code to the application itself.

Consider an application that keeps some data on the filesystem instead of a database. For example, a multilingual site that keeps localizations in files. Perhaps the home page code looks like this:

<?

function localize($content, $lang) {

return fread("../config/lang/"+$lang+"/"+$content);

}

?>

<html>

<head><title><?= localize($_GET("pg")+".title",$_GET("hl"))?></title></head>

<body><?= localize($_GET("pg"), $_GET("hl"))?></body>

</html>Note that it takes parameters from the URL string and uses them to read files off the filesystem, including their content in the page.

When you load up http://www.example.com/?hl=en-us&pg=main, the server looks for ../config/lang/en-us/main.title and ../config/lang/en-us/main. Perhaps the resulting HTML looks like this:

<html>

<head><title>Cool site: Main</title></head>

<body><h1>Hello, world!</h1></body>

</html>Now, what happens if instead, we visit http://www.example.com/?hl=../../../../../../../../&pg=../etc/passwd? The site will look for ../config/lang/../../../../../../../../&pg=../etc/passwd.title and ../config/lang/../../../../../../../../&pg=../etc/passwd. It’s unlikely to find the first one, but assuming the server ignored the error, we might get a web page that looks like:

<html>

<head><title></title></head>

<body>nobody:*:-2:-2:Unprivileged User:/var/empty:/usr/bin/false

root:*:0:0:System Administrator:/var/root:/bin/sh

daemon:*:1:1:System Services:/var/root:/usr/bin/false

</body>

</html>On any modern Unix-like system, grabbing /etc/passwd isn’t a big deal, but if the the attacker managed to brute force other files on the system (perhaps a config file or something like /home/dev/vpn-credentials.txt), the results could be quite bad. Even worse would be a site that allows users to upload files, but the user can manipulate the file location to be code (e.g. .php, .asp, etc.) inside the web root. In this case, the attacker can upload a web shell and run commands on the web server.

Log into your DVWA and make sure the security level is set to low. Navigate to the “File Inclusion” page, and experiment with the URL that you visit when you click on a file. Can you retrieve the /etc/passwd file?

To a large extent, the best advice for preventing this sort of attack is “don’t use the filesystem in your application code.” While this advice is effective, it’s not always practical. A hybrid option would be to store file names in a database, and accept database indices from the user. In the above example, perhaps the database would look something like:

| lang | page | type | location |

en-us | main | title | ../config/lang/en-us/main.title |

en-us | main | body | ../config/lang/en-us/main |

If this isn’t feasible, the site should only use and accept a very limited set of characters (such as letters and numbers) for user-specified filename components. This will still likely allow users to read or write arbitrary files within a specified directory, so the application developers must ensure that files in that directory aren’t executable by the web server, and that there is no sensitive data or important configuration information in that directory.

For a bit more on path injection, see the OWASP guide on it. For an in-depth exploration, see the Web Application Security Assessment learning path.

Shell injection is similar to path injection, in that it involves the application’s interactions with the operating system. In this case, though, the application is directly executing a shell command or several commands, and it’s possible for an attacker to change what commands are executed. The impact of a shell injection is extremely high, allowing the attacker to run their own commands on the underlying web server hardware. Complete compromise of the web application is almost assured. Given time, compromise of other infrastructure in the server environment is likely.

Consider an application that allows users to check network connectivity to other systems from the web server. Here’s some code for a minimal PHP page that does this:

<html>

<head><title>Network connectivity check</title></head>

<body>

<h1>Network connectivity check</h1>

<form method="GET">

<input name="host">

<input type="submit">

</form>

<?

if ($_GET("host")) {

print(" <h2>Results</h2>\r<pre>".shell_exec("ping -c 3 ".$_GET("host"))."</pre>");

}

?>

</body>

</html>If the users enters “8.8.8.8”, the page uses the shell_exec function to run the command ping -c 3 8.8.8.8, and the resulting HTML looks something like this:

<html>

<head><title>Network connectivity check</title></head>

<body>

<h1>Network connectivity check</h1>

<form method="GET">

<input name="host">

<input type="submit">

</form>

<h2>Results</h2>

<pre>PING 8.8.8.8 (8.8.8.8): 56 data bytes

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=0 ttl=119 time=7.266 ms

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=1 ttl=119 time=8.681 ms

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=2 ttl=119 time=12.481 ms

--- 8.8.8.8 ping statistics ---

3 packets transmitted, 3 packets received, 0.0% packet loss

round-trip min/avg/max/stddev = 7.266/9.476/12.481/2.202 ms</pre>

</body>

</html>Super handy! However, what will happen if the user enters “8.8.8.8; ls -1 /” instead? The shell command run will be ping -c 3 8.8.8.8; ls -1 /, and the resulting web page will look something like:

<html>

<head><title>Network connectivity check</title></head>

<body>

<h1>Network connectivity check</h1>

<form method="GET">

<input name="host">

<input type="submit">

</form>

<h2>Results</h2>

<pre>PING 8.8.8.8 (8.8.8.8): 56 data bytes

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=0 ttl=119 time=5.611 ms

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=1 ttl=119 time=11.918 ms

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=2 ttl=119 time=9.519 ms

--- 8.8.8.8 ping statistics ---

3 packets transmitted, 3 packets received, 0.0% packet loss

round-trip min/avg/max/stddev = 5.611/9.016/11.918/2.599 ms

Applications

Library

System

Users

Volumes

bin

cores

dev

etc

home

opt

private

sbin

tmp

usr

var</pre>

</body>

</html>What happened? The shell saw the command to ping 8.8.8.8, and then a semicolon. In most Unix-like shells, the semicolon command separates individual commands that are run together on one line. So, the shell ran the ping command, then ran the next command, to list the root directory contents. It gathered the output of both commands, and then returned those results to the web server.

Obviously, something like this could be used to retrieve almost any file from the web server (for example, using the “cat” command). The attacker could cause the web server to download files (including executables) from other servers, and then run those commands. Those downloaded executables could be exploits that allow the attacker to escalate privileges from the web server user to an administrative user (e.g. system or root), giving the attacker full control over the web server.

Log into your DVWA and make sure the security level is set to low. Navigate to the “Command Injection” page, and experiment with the input. Can you list the contents of the web server’s root directory?

As with path injection, the best way to prevent shell injection is “don’t do that.” Unlike with path injection, the advice to not run shell commands from the web server should not be given full consideration. The other alternatives (such as input data validation) are difficult to implement correctly, and may be impossible if the application needs to allow any sort of non-trivial input.

For a bit more on shell injection, see the OWASP guide on it and the OWASP guide on preventing it. For an in-depth exploration, see the Web Application Security Assessment learning path.

(This is a recap of the exercise outlined above in the subtopic)

Access your installation of DVWA. Set the difficulty level to “low” and complete the following sections:

For each of the following sections, your task is to find and exploit the vulnerability as described on the respective DVWA page. Since you might not have a lot of experience with JavaScript, SQL, or command lines, it is totally all right to use walkthroughs (there are many online that look at DVWA) or guides to aid you in the exercises. Just make sure that, rather than simply copying and pasting commands from the walkthroughs, you can actually explain what each DVWA page does and what the vulnerability is.

Data validation is a critical aspect of web application security, ensuring that input data is safe, properly formatted, and free from malicious intent. Failure to implement adequate data validation can leave web applications vulnerable to various exploits. The following questions explore the importance of data validation in web applications and techniques for preventing data validation vulnerabilities.

If possible, discuss your answers to those questions with a peer or mentor who will help verify that you’ve correctly understood the topic.

Question 1

What is a common consequence of failing to implement proper data validation in a web application?

A) Increased server performance

B) Enhanced user experience

C) Vulnerability to SQL injection attacks

D) Improved data integrity

Question 1 correct answer: C) Vulnerability to SQL injection attacks

Explanation:

A) Incorrect. Failing to implement proper data validation typically does not lead to increased server performance.

B) Incorrect. While proper data validation contributes to a better user experience by preventing errors, its absence does not enhance user experience.

C) Correct. Without proper data validation, web applications are vulnerable to SQL injection attacks, where attackers can manipulate database queries by injecting malicious SQL code.

D) Incorrect. Data validation helps maintain data integrity, but its absence does not improve data integrity.

Question 2

Which of the following is an effective mechanism for preventing cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks in web applications?

A) Using plaintext for storing sensitive data

B) Escaping user input before displaying it

C) Storing user passwords in plain text

D) Disabling HTTPS encryption

Question 2 Correct Answer: B) Escaping user input before displaying it

Explanation:

A) Incorrect. Using plaintext for storing sensitive data does not prevent XSS attacks; in fact, it increases the risk of data exposure.

B) Correct. Escaping user input before displaying it helps mitigate XSS attacks by rendering any potentially malicious scripts harmless, thereby preventing them from executing in users’ browsers.

C) Incorrect. Storing user passwords in plaintext is a security risk and unrelated to preventing XSS attacks.

D) Incorrect. Disabling HTTPS encryption exposes sensitive data to interception and does not prevent XSS attacks.

Question 3

Which technique is effective in preventing SQL injection attacks in web applications?

A) Using dynamic SQL queries

B) Employing input sanitization and parameterized queries

C) Storing sensitive data in plain text

D) Disabling error messages

Question 3 Correct Answer: B) Employing input sanitization and parameterized queries

Explanation:

A) Incorrect. Using dynamic SQL queries without proper input validation and sanitization increases the risk of SQL injection attacks.

B) Correct. Employing input sanitization and parameterized queries helps prevent SQL injection attacks by ensuring that user input is treated as data rather than executable code, thus neutralizing malicious SQL injection attempts.

C) Incorrect. Storing sensitive data in plain text increases the risk of data exposure but does not directly prevent SQL injection attacks.

D) Incorrect. Disabling error messages may hide potential vulnerabilities from attackers but does not address the root cause of SQL injection vulnerabilities.

Question 4

Which of the following statements best explains how proper data validation helps prevent command injection attacks in web application security?

A) Data validation restricts the input to predefined characters and patterns, thereby minimizing the likelihood of malicious commands being injected into the application.

B) Proper validation techniques, such as input sanitization and parameterized queries, help neutralize malicious commands embedded in user inputs, thereby mitigating command injection vulnerabilities.

C) Implementing validation methods like input length checks and whitelisting of acceptable characters reduces the attack surface and prevents execution of unauthorized commands within the web application.

D) All of the above.

OWASP guides to vulnerabilities: SQL Injection

FreeGreat overviews of different vulnerabilities, including examples.

OWASP guides to vulnerabilities: XSS

FreeGreat overviews of different vulnerabilities, including examples.

OWASP guides to vulnerabilities: Path traversal

FreeGreat overviews of different vulnerabilities, including examples.

OWASP guides to vulnerabilities: Command injection

FreeGreat overviews of different vulnerabilities, including examples.

OS command injection cheat sheet

FreeQuick overview of different OS commands which could be abused for injection.

Web shells

FreeOverview of what a web shell is and how it could be used in attacks.

Congratulations on finishing Module 2!

Mark the checkbox to confirm your completion and continue to the next module.

Marks the current module as completed and saves the progress for the user.

You've completed all modules in this learning path.