Module 6

Refining Your Web Application Testing Process

Last updated on: 28 August 2024

Edit this page on GitHubModule 6

Last updated on: 28 August 2024

Edit this page on GitHubSubtopic 5 is a prerequisite for this one, and learners are strongly encouraged to thoroughly read it before proceeding.

If you’re like most people, you struggled with the last practice. It probably took you a long time, and you probably missed a bunch of vulnerabilities. Don’t be dispirited! Before you started this, you would’ve found far fewer in far more time. It may not feel great, but it’s very difficult to transition from learning about vulnerabilities in isolation to finding them in an open-ended environment. So, struggling and not being super-successful is part of the process.

Once you’ve figured out the fundamentals of finding vulnerabilities in websites, this subtopic will teach you a process to find those vulnerabilities more quickly and efficiently.

After completing this subtopic, practitioners should be able to understand a methodical approach to web application security assessment that results in finding more vulnerabilities in less time.

There are a few common pitfalls that trap new web application testers. Think about whether you fell victim to any of these while testing Juice Shop:

If you did any of these things, don’t feel bad. Most people struggle with these, often through full careers as professional web application testers. What you can do is develop strategies to avoid these (and other) issues that make your testing slow and unreliable. This subtopic will show you a few strategies to get you started.

In the last subtopic, we introduced the concept of a methodology for web applications security assessments,a way of organizing and thinking about testing. Now, we’re going to reframe that framework into a process. The problem with a framework is that it’s too general. You can test any web application using the framework, but for any specific application, you’ll be more successful if you give yourself more structure.

When testing a website, you’ll usually want two users at each level of access, though this can vary. Consider an online forum. You’ll want two registered users, one or two moderators, and one or two admin users. This will let you fully test the site’s authorization controls. In the above example, things you might want to test include:

If you were testing a forum website that allowed multiple sub-forums, you might need 3 normal users (two assigned to sub-forum A and one from sub-forum B), two moderators and admins (one for each sub-forum) and a super-admin.

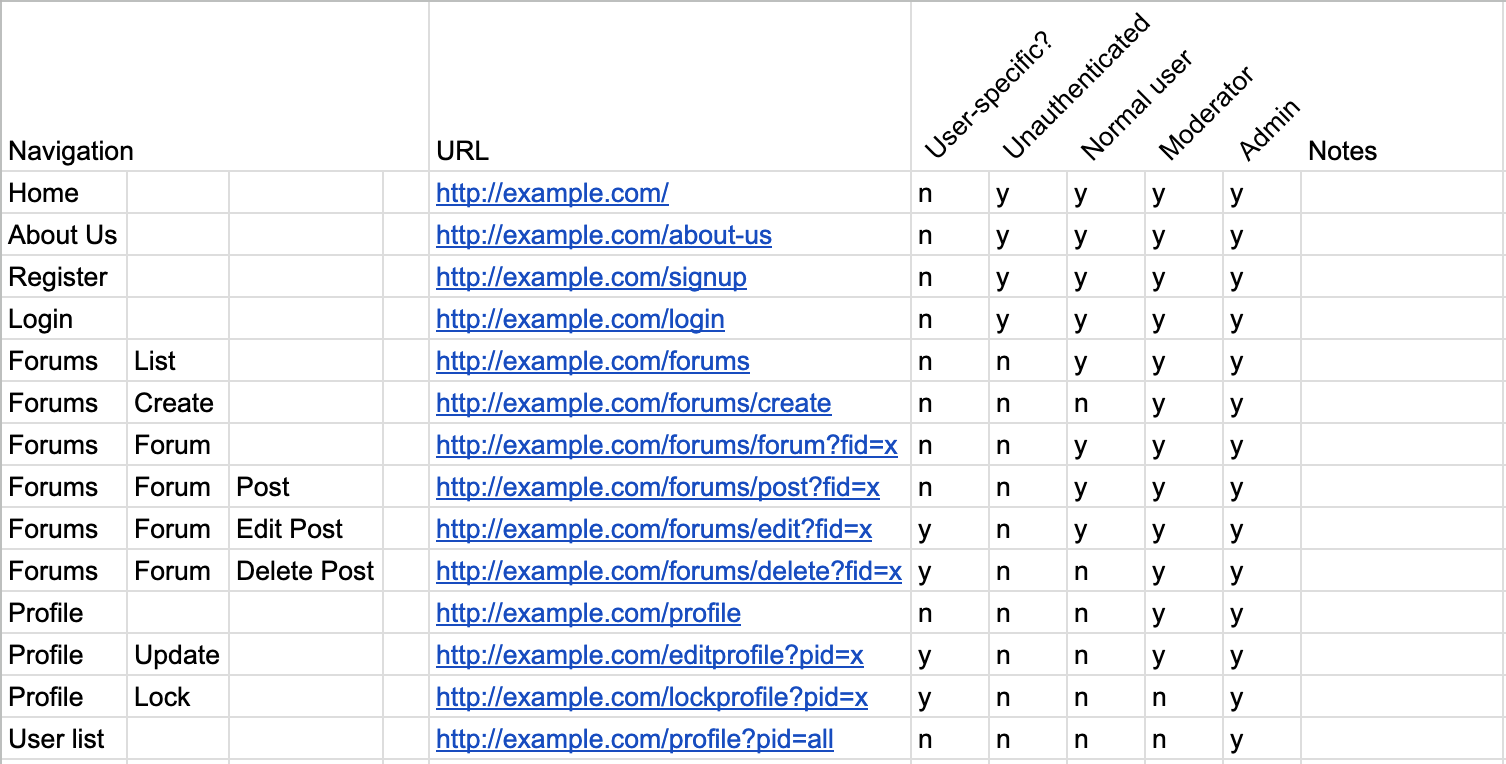

Once you’ve got the user accounts you need, you can start making a site map. The site map will guide your testing, and will function as your checklist for testing. As as example, you might produce something like this:

This shows every page you’ve found in the app (“URL” column), its logical navigation, whether the content of the page changes depending on its parameters (“User-specific?” column), and then whether each user type has access to the URL. There’s also a “notes” column for you to collect important info about the page, e.g., if the profile page shows very different content depending on the user of the person viewing the page or if data input on one page shows up on another. Some sites may not fit nicely into this particular structure. That’s fine, the structure should be specific to the site, so feel free to change it. However, something like this should work for most sites.

In building this spreadsheet, you need to go through all the pages on the site and all the site’s user roles. This is most of the Discovery section of the web methodology used in the previous subtopic. So, obviously, while you’re building the site map, you should make sure you complete all of the Discovery tests.

⚠️ This part of the process is extremely important, but can be very dull. To liven it up, do a little ad-hoc testing while you’re going through the site. Maybe check an input for XSS here, do a little authorization check there. This will help keep you engaged while you go through the site.

Certain parts of the methodology apply to the entire site, or a few places on the site. Every web server has a configuration, and most websites have 1 to a few logical servers (e.g. www.example.com, api.example.com, static.example.com). Most sites have one (or maybe two) login/registration/account management sections and session management mechanisms. You should do these tests next. Doing so will let you feel productive by completing multiple methodology sections quickly, and will give you a chance to understand the structural underpinnings of the website. As you do these tests, you might find more web pages that you originally missed. If so, that’s fine, but be sure to add them to your spreadsheet!

Most people elect to keep their notes from these tests in a text file, as opposed to their testing spreadsheet, but do whatever feels natural to you.

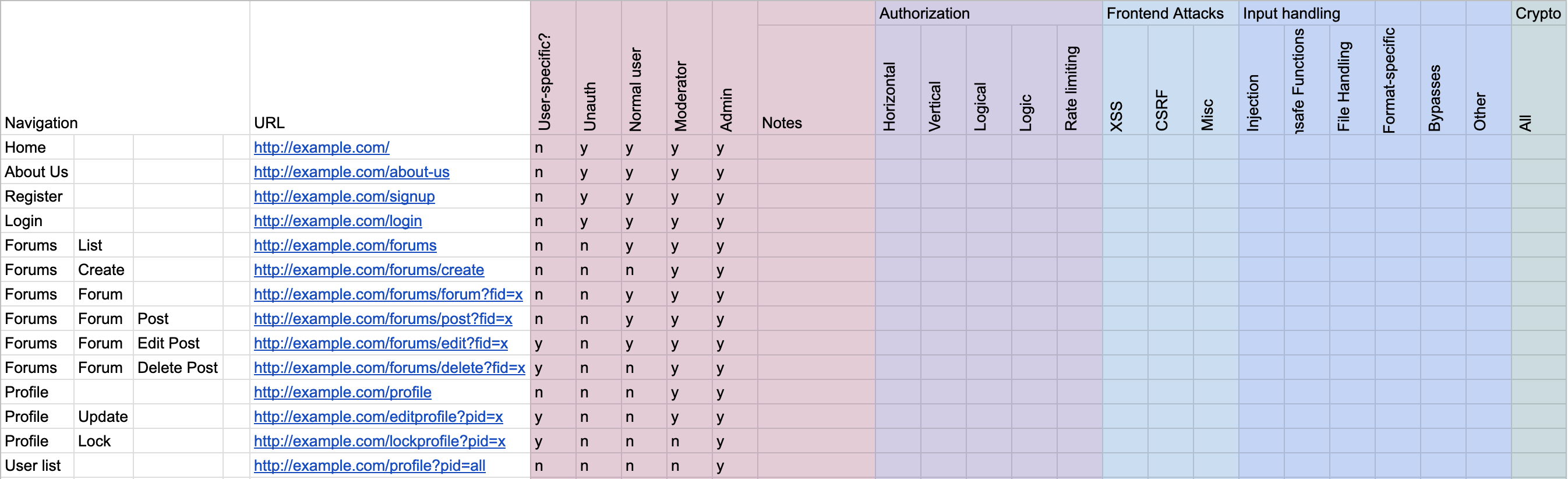

Now that you understand the site, you can dive into the biggest part of testing the site: testing every page (and every input) for the full battery of tests in the rest of the methodology. This is going to be a lot to keep track of, and if you don’t stay focused and keep track, you will miss things. Fortunately, you’ve prepared a spreadsheet. All you need to do is expand that spreadsheet and you’ve got a full checklist:

This might seem daunting, but every cell in that sheet is a small, discrete chunk of work that should take a bounded amount of time. It’s usually more effective to go through the site filling out rows first; choose a page and go through the entire methodology, rather than performing one test throughout the entire site. As you go, put something like a “√” in cells as you complete them, or something like “n/a” if the tests don’t apply. Over the hours and days, your checklist will get filled in, and you can be confident that you’ve performed complete testing.

⚠️ It’s a good idea to keep separate notes in your regular notes document while you do this testing, you want to keep your spreadsheet clean and clear.

Getting fixated on a particular page/input/etc while testing, and spending hours on it is a near-universal mistake among people who test web applications. They tell themselves that they’re at the cusp of a breakthrough, and they’ll be done in 10 minutes. Next thing they know, it’s two hours later and they forgot to eat lunch. (Not everyone does this. But if you do, you’re in good company.) If you have infinite time to test a site, then this isn’t much of a problem (missed meals notwithstanding). Most of the time, though, you have limited time. If you run out of time because you got fixated on one page, you may leave entire swaths of the site, riddled with vulnerabilities, untested.

If you find yourself getting stuck frequently, set a timer every time you start a cell in the testing spreadsheet. Make sure you can’t see the timer, looking at a clock countdown is stressful. With experience, you will be able to guess how long a cell should take. Give yourself a nice buffer (around 50% or more). So, if you think you can complete a cell in 10 minutes, set a timer for 15 or 20 minutes. The idea is for the timer to warn you that maybe you’re fixated, not to motivate you to go fast. If the timer goes off before you finish the cell, stop and evaluate. If you found a vulnerability and are making progress creating a demonstration exploit (e.g., you find SQL injection and you’re setting up something to extract the database), then reset the timer and keep going. If, however, you find that you’re chasing after some vulnerability that maybe doesn’t actually exist, then take a note about your progress to date, and move on to the next cell. If you have time at the end of testing, you’ll be able to come back.

This strategy also has good health benefits. The process of resetting the timer per cell also gives you an opportunity to get up and stretch, get a beverage, make sure you break for meals, etc.

This strategy was discussed in the previous section, but most people ignore the advice at first. Hopefully, in the process of completing the previous section, you either followed the advice, or you learned that writing the report at the end is not an effective strategy. Many people have to learn this lesson repeatedly through an entire career doing security testing, so don’t feel too bad if you mess up from time to time.

Related to this, you want to keep effective notes. Many people keep a running notes file that just includes everything they think of and odd things they notice during testing, and another notes file that includes further details about vulnerabilities that they find and conclusions about the site that are too verbose or unfined to the report.

These strategies should set you up for success in testing websites. We’ll put them into practice in the next subsection of this subtopic.

The OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) Model serves as a standardized framework for understanding computer networking theory, although real-world networking is predominantly based on the more concise TCP/IP model. Nonetheless, the OSI model remains valuable for gaining an initial grasp of networking concepts. These layers collectively enable the smooth functioning of computer networks, ensuring efficient and reliable data transmission from the application to the physical hardware level.

Since the OSI model is one of the main ways in which we think about networking, it’s useful to be familiar with it when thinking of and looking for potential vulnerabilities as well.

| Layer | Name |

|---|---|

| layer 7 | APPLICATION |

| layer 6 | PRESENTATION |

| layer 5 | SESSION |

| layer 4 | TRANSPORT |

| layer 3 | NETWORK |

| layer 2 | DATA LINK |

| layer 1 | PHYSICAL |

The OSI model comprises seven layers:

Attackers can breach each OSI model layer due to inherent vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities can arise from software bugs, design flaws, and misconfigurations, which collectively provide attackers with opportunities to exploit weaknesses across all seven layers.

This practice is similar to that of the previous subsection, except this time you’ll be following the testing process outlined above. Also, the website you’ll be testing is a bit more realistic; it was built to be a website with vulnerabilities, as opposed to a site containing a bunch of challenges. As such, it should feel more like testing a real website does.

If you have a mentor, review your report with them. You will probably find it useful to look at a list of the vulnerabilities present in DIWA available (please submit any additions). If you’ve found the majority of those in a reasonable amount of time (1-2 days), then congratulations!

If you don’t have a mentor, you can self-review using the list above.

Congratulations on finishing Module 6!

Mark the checkbox to confirm your completion and continue to the next module.

Marks the current module as completed and saves the progress for the user.

You've completed all modules in this learning path.